my untamable tbr piles

An attempt at putting some order to my truly out-of-control tbr piles earlier this month turned into a bookcase-reorganization project that took up a good part of my time on the first summer Friday of the year. My plans for summer reading are probably still too ambitious, and every book I read seems to suggest two or three other books I ought to read, so who knows what I’ll actually read and how well (if at all) it will correspond with my plans.

For example, I checked out The True Story of the Novel by Margaret Anne Doody from the library a few weeks ago just so I could read the introduction and get a sense of her overall argument. I knew that in the book Doody proposes that the origins of the novel are found not in eighteenth-century England or Don Quixote but many centuries ago in ancient Greece and Rome, and I was prepared to dismiss her argument because how can we say that a thing we call the novel existed long before the word novel came into use? Instead, I found her argument, at least as it is presented in the introduction, heady and seductive. Doody takes on the arguments and assumptions of Watt, Bakhtin, Lukács, Kermode, Auerbach, and so on and on, as well as the construction of the Western canon and the idea that individual personhood is a modern, bourgeois construction. She writes:

At times one encounters a strange kind of anti-pastoral pastoralism that feels a nostalgia for an era when we were innocent of personality, and also innocent of erotic love—when we did not have to cope with the heavy intricacies of (modern) breathing human passion. . . . If love is a conspiracy, it is much older than the age of “bourgeois individualism” in which some historians tend to locate it; nostalgia for an age that knew no Eros is hard put to find a home. There has admittedly been a tendency for classicists to present their age as secure from that awkward feminizing influence. Plato’s Eros, is after all, homosexual, but Socrates does not indulge it, and Love between persons, being only a matter of beauty, should be but the first rung in the ladder that leads to higher things. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche and C. S. Lewis have perhaps nothing else in common, but they both share the nineteenth century’s desire to keep the grand classical age free of love stories. I was taught by C. S. Lewis, through reading his The Allegory of Love (1936), that what we know as “romantic love,” heterosexual eroticism with an emphasis on personal emotions, began in the Middle Ages.

Instead, argues Doody, “‘Romantic love,’ with the poetic conceits that express it, is much, much older than the Middle Ages, and there is a great continuity in our dealings with it.” This argument for antiquity and continuity rings true to me. After all, the readings for the course I took in college on sexuality and spirituality (that is, the elements of romantic love) in the middle ages and Renaissance began not with medieval poetry but with the Song of Songs and Ovid. And, of course, there’s Sappho (from the translation by Anne Carson of fragment 31):

. . . oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead — or almost

I seem to me. . . .

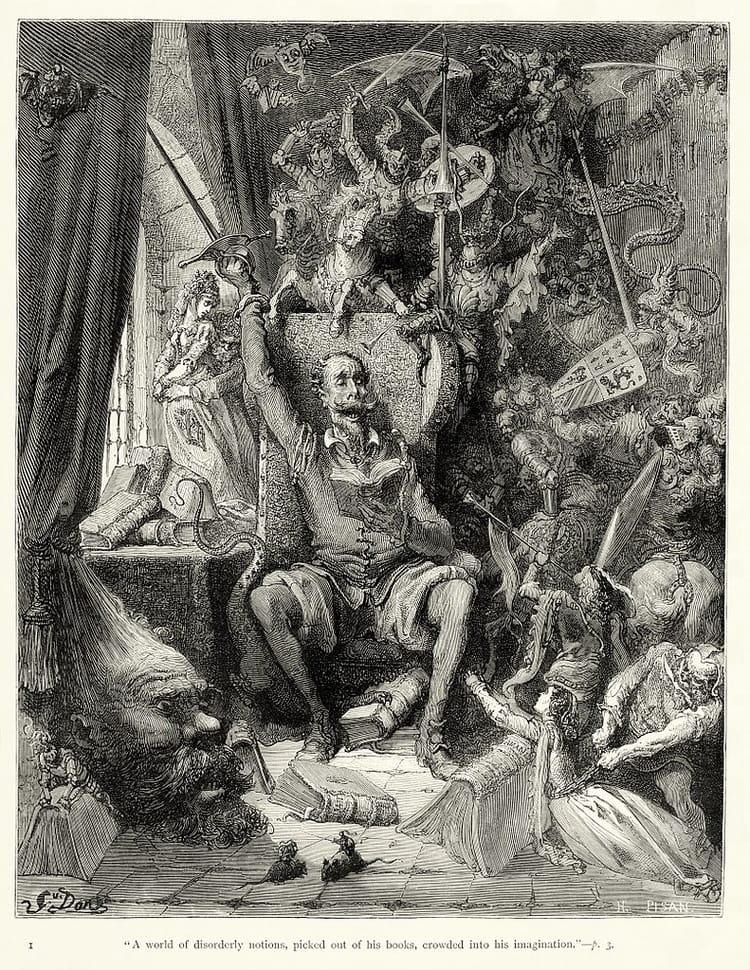

I have dozens of other books to read: a short-story collection to review; Dune, which I stopped reading about 100 pages short of the ending because I know I don’t like how the book concludes; three Ukrainian novels plus A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian, which I found on the sidewalk on my way to pick up the 12yo from after-school; a tall stack of romances; a shorter stack of poetry collections; and Don Quixote, which I’m determined to get to the end of on this reread. And there’s more. All the same, how can I not read the nearly 500 packed pages of The True Story of the Novel right now? I mean, I was planning to get back to it eventually, but . . .