the loose, baggy monster

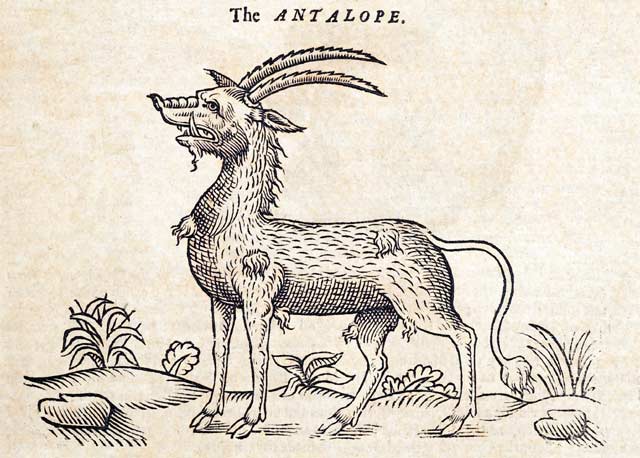

In library school, we were frequently asked to consider such definitional questions as What is information? and What is a book? In two different courses I encountered the question of whether an antelope is a document, both times in the article “Information as Thing,” in which Michael K. Buckland, citing the views of Suzanne Briet, writes: “A wild antelope would not be a document, but a captured specimen of a newly discovered species that was being studied, described, and exhibited in a zoo would not only have become a document, but ‘the catalogued antelope is a primary document and other documents are secondary and derived.’”

I admire the mind that can take up such a question and respond with such clarity and thoroughness, though I also find it suspect; the catalogued antelope is obviously a colonial subject. Mine is not such a mind. When I taught poetry writing workshops, for example, students often asked But what is poetry, particularly in discussions of prose poetry or of metered versus free verse poetry, and over time I lost interest in this question. What eventually seemed more useful than trying to categorize a given work as poetry or not poetry was describing its traits so that I might consider how those traits function in the work and how I might employ those techniques myself. Traits of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, for example, include its matter-of-fact narrator, who is deeply sad but takes a stance of curiosity toward her sadness. The book incorporates elements of both memoir and philosophy, particularly aesthetics. It is brief, comprising only 95 short pages, and written in prose, organized in numbered sections after the example of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s propositions. Is it poetry? Who knows? As a reader, writer, and teacher of poetry, I don’t have to decide.1

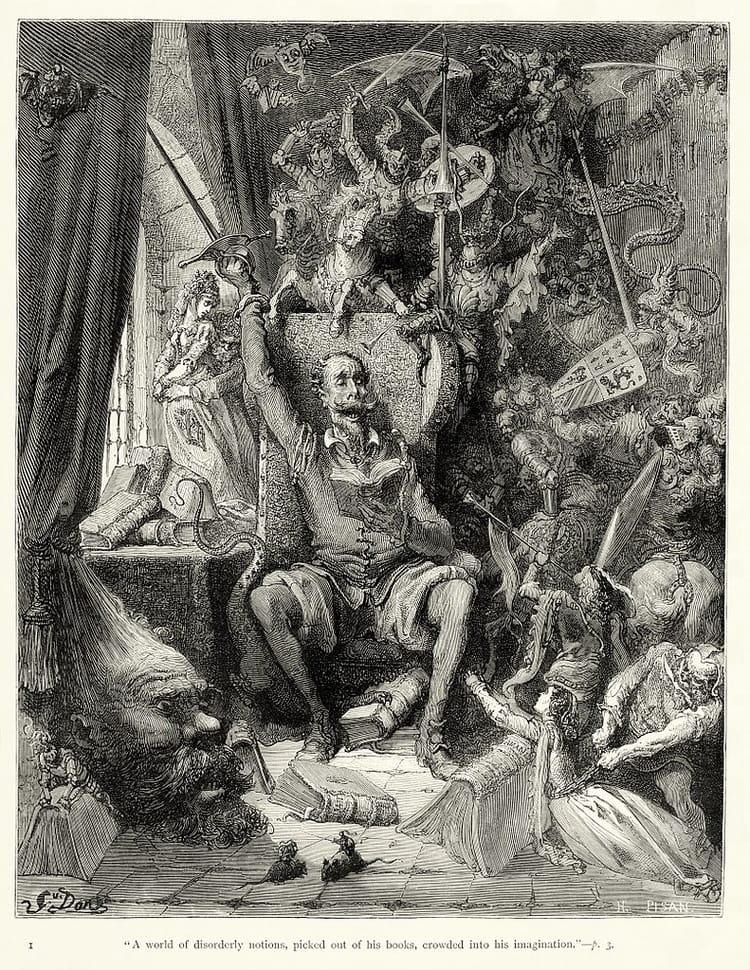

Despite my skepticism about definitions, when reading the literature on Don Quixote, I did wish that I could find an origin for the thing we call the novel. Many people have said that Don Quixote is the first novel, and it has always seemed telling to me, if not inauspicious, that what might be the first novel is the story of a man driven mad by reading. Not everyone agrees that Don Quixote was the first, however. Roberto Gonzáles Echevarría, for example, calls it the first modern novel. Ian Watt says that Robinson Crusoe, published more than a century after Don Quixote, was the first novel. And Margaret Anne Doody begins her book The True Story of the Novel with the bold claim, “This book is the revelation of a very well-kept secret: that the Novel as a form of literature in the West has a continuous history of about two thousand years.”

I like the capaciousness of Doody’s outlook. She writes:

I believe that a novel includes the idea of length (preferably forty or more pages), and that, above all, it should be in prose. . . . If anybody has called a work a novel at any time, that is sufficient—so Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Voltaire’s Candide, J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, can all be admitted. When we are trying to discover what a genre might be (and the idea of “genre” is itself at once loose and arbitrary ) it is too soon to impose strict definitions and qualifications. Nothing is precluded by my theory, which comes not to destroy but to fulfill.

I also like Henry James’s description of the novel as a “loose, baggy monster.” This vision of the genre as monstrous jibes with an account that Timothy Snyder gives of origin stories—that we should be suspicious of origin stories that imagine a past state of innocence and purity (e.g., the Garden of Eden) and instead think of origins as arising from encounters like those in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which tells stories about “weird contacts involving violence and sex and families that generally don’t work out” but do result in transformations.

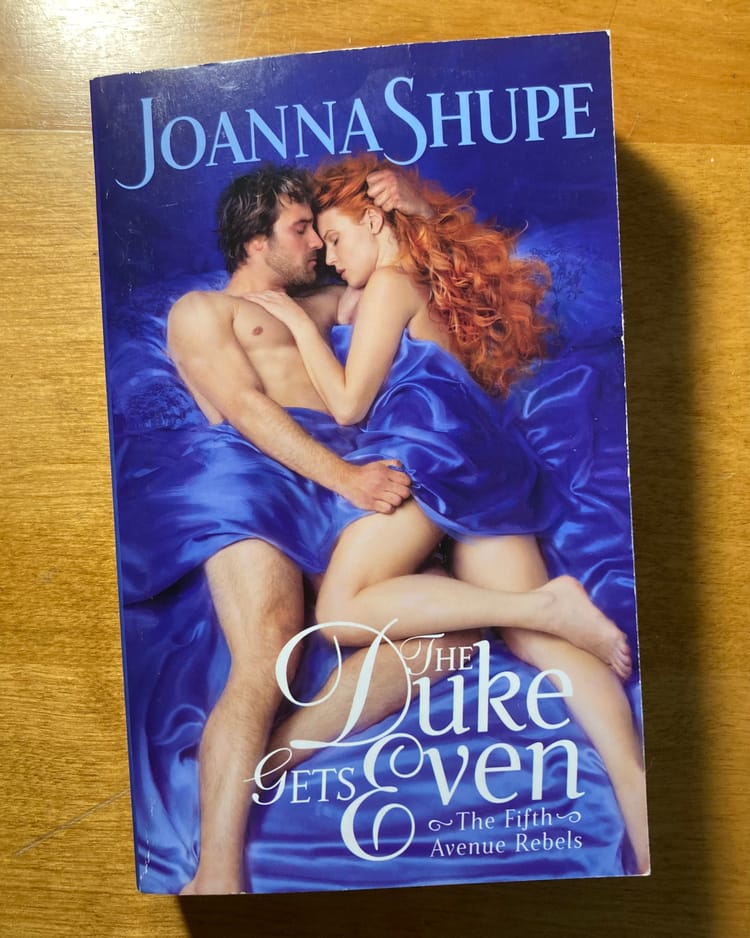

And so it would appear that my conclusion is that the novel is a prosy monster of indefinite origin, and definitions don’t matter much anyway, so who cares whether or not Don Quixote was the first novel. I certainly don’t, not anymore. But next time I want to take a bit of a detour to tell an origin story of sorts—the story of my beginnings as a reader of romance novels, the definition of which matters very much.

The cataloguer, by the way, does have to decide. In a library classification system, the book must be assigned just one number, so that it can be placed and found in one and only one spot on a shelf of a library. In the Dewey Decimal Classification, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets is assigned 811: American poetry in English. ↩