on picking and choosing

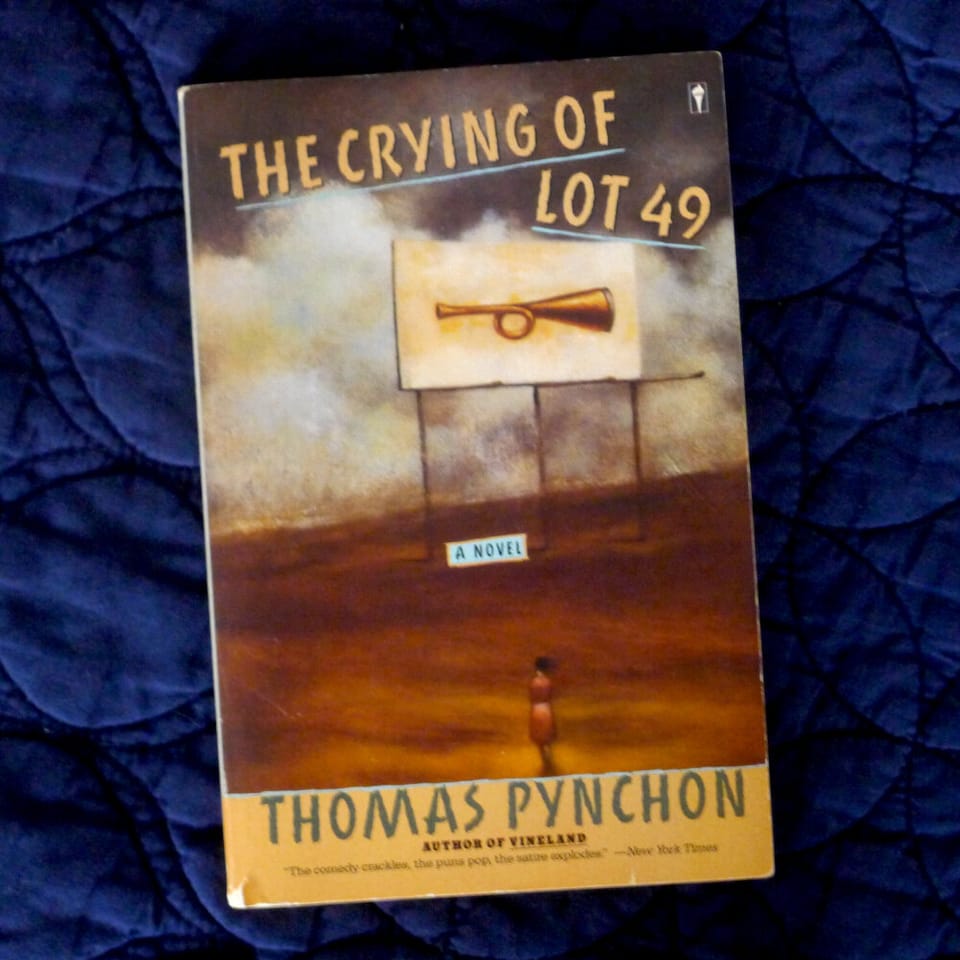

Maxwell’s Demon, a being postulated by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell in his 1871 book Theory of Heat, plays a central role in The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon and is explained to Oedipa Mass, the protagonist, by Yoyodyne employee Stanley Koteks as follows:

The Demon could sit in a box among air molecules that were moving at all different random speeds, and sort out the fast molecules from the slow ones. Fast molecules have more energy than slow ones. Concentrate enough of them in one place and you have a region of high temperature. You can then use the difference in temperature between this hot region of the box and any cooler region, to drive a heat engine. Since the Demon only sat and sorted, you wouldn’t have put any real work into the system. So you would be violating the Second Law of Thermodynamics getting something for nothing, causing perpetual motion.

It has always baffled me that in this scenario our little information specialist, the Demon, is said not to be working; Oedipa, too, objects: “Sorting isn’t work? Tell them down at the post office, you’ll find yourself in a mailbag headed for Fairbanks, Alaska, without even a FRAGILE sticker going for you.” In my view, this sorting not only is only work, but in fact is anxiety-provoking work because in sorting molecules according to their temperature, the Demon has only two options: fast or slow. But what about the ambiguous cases? Which molecules are too slow to be fast? Which are too fast to be slow? Where is the line to be drawn between “fast” and “slow”? And what is to be done about molecules that are just on that line, neither fast nor slow?

I’m too anxious to be the Demon. Similarly, when my students ask me But what is poetry? I tend to turn the discussion toward a more clear-cut topic: distinguishing verse from prose rather than poetry from prose. Defining poetry doesn’t interest me much, actually, because doing so (or trying to do so) doesn’t help me actually write poetry.

Despite my resistance to sorting, the Faith Mind Poem of Jianzhi Sengcan, the third ancestor of Zen, presents a challenge to me. The poem begins:

The Great Way is not difficult

for those who avoid picking and choosing.

Or, as another translation says:

The Great Way is not difficult

for those who have no preferences.

The tension between these two lines has always struck me as a bad joke. Just give up your preferences! No big deal!

And yet … I find lately that my preferences are hidden from me. Which is not to say that I am now walking the Great Way with ease! Hardly. What I mean is that I have a hard time knowing what to say “no” to and what to say “yes” to. Indeed, like many women, I feel obliged to say “yes” to too much. How is the Great Way for those who have difficulty picking and choosing?