what is wisdom?

Since last summer I’ve been a student in the Graduate School of Library and Information Studies at Queens College. Preparing for a career change in middle age feels aberrant in itself; preparing for a career change in the midst of a pandemic feels foolish. But trying to maintain my current career much further feels even more unsustainable, so.

This semester I am taking Fundamentals of Library and Information Science—my third class in the program, probably should have been my first, but oh well—and am feeling that, despite my anxieties as a Humanities person in a Social Sciences arena, I am very much in the right place, given that the first two questions my professor asked in his first lecture were What is reality? and What is knowledge? Evidently there is no clear, widely accepted definition of the word information, even in the field Information Studies, and so our first task in the class was to write a paper answering the question What is information? so that we might come to our own definition of the term for ourselves. Among my discoveries while writing the paper—discoveries that didn’t even make it into the paper, which as it was turned out to be nearly twice the minimum length required by the teacher!—were that my thinking about ontology and epistemology are even more deeply informed by Buddhism than I realized, and that my definition of wisdom appears to have nothing at all to do with how it is defined in the academic literature.

Our textbook readings present data, information, knowledge, and wisdom as arranged in a hierarchy or “conceptual ladder” in which raw and unprocessed data become information, which “increases knowledge that results in wisdom to benefit society” (p. 385 in Foundations of library and information science by Rubin & Rubin). This framework is nonsensical; as I wrote in my paper, “By presenting data as flowing toward wisdom, this framework seems to leave out the reality that organizing data so that it may be informative, and in turn giving meaning to that information, is itself an informed process. Knowledge, such as a method or set of principles, is not only created but also applied in that process.”

I am more interested in information and knowledge as understood by Marcia J. Bates in “Fundamental Forms of Information” and Susantha Goonatilake, whose concept of “information flow lineages,” including a genetic lineage with prebiotic origins, Bates cites in her work. Their understanding of information and knowledge encompasses the kind of knowledge that we know without knowing that we know it: we know how to keep our hearts beating, for example.

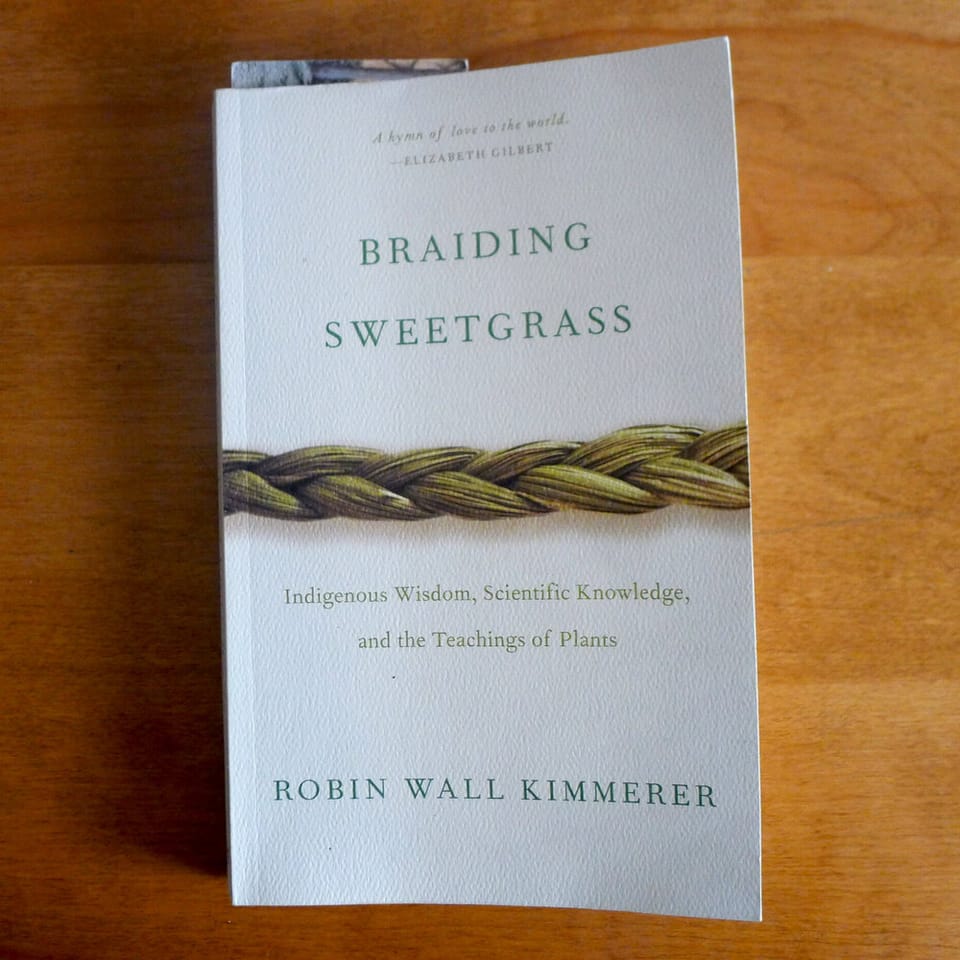

In my understanding, wisdom flows from this sort of lineage: it is networked, or, to use Goonatilake’s word, ecological. From Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, on the wisdom of pecan trees:

For mast fruiting to succeed in generating new forests, each tree has to make lots and lots of nets—so many that it overwhelms the would-be seed predators. If a tree just plodded along making a few nuts every year, they’d all get eaten and there would be no next generation of pecans. But given the high caloric value of nuts, the trees can’t afford this outpouring every year—they have to save up for it, as a family saves up for a special event. Mast-fruiting trees spend years making sugar, and rather than spending it little by little, they stick it under the proverbial mattress, banking calories as starch in their roots.

… But trees grow and accumulate calories at different rates depending on their habitats. So, like the settlers who got the fertile farmland, the fortunate ones would get rich quickly and fruit often, while their shaded neighbors would struggle and only rarely have an abundance, waiting for years to reproduce. If this were true, each tree would fruit on its own schedule, predictable by the size of its reserves of stored starch. But they don’t. If one tree fruits, they all fruit—there are no soloists. Not one tree in a grove, but the whole grove; not one grove in the forest, but every grove; all across the county and all across the state. The trees act not as individuals, but somehow as a collective.

This collective action is the enacting of wisdom, which, writes Kimmerer, supports mutual flourishing.

I’ve written

Since I last posted—ages ago!—I’ve written for the Ploughshares blog about Irish writer Molly Aitken’s debut novel, Elena Ferrante’s latest novel, the “unlikeable” protagonist of Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys, emptiness and Red Pill by Hari Kunzru, my family lexicon, and In the Company of Men by Véronique Tadjo, which features the wisdom of “Baobab, the first tree, the everlasting tree, the totem tree.”

Also, I have a poem, “Where Do We Come From, Where Are We Going?” in the wonderful debut issue of DEAR, a poetry journal “comprised of dedications to people, places, and things.”